ports of entry: language in caribbean migrations

More people, in sheer numbers, are displaced from their homes now than ever before in history, with nearly 1 in every 69 people migrating. In the past decade alone, the number of refugees worldwide has tripled and the number of asylum seekers has more than quadrupled. Since migrants are on the frontlines of language contact, their speech communities are among the primary agents of linguistic change. Anthropologists and policy makers alike require a more nuanced understanding of the key role that language plays in the migration experience.

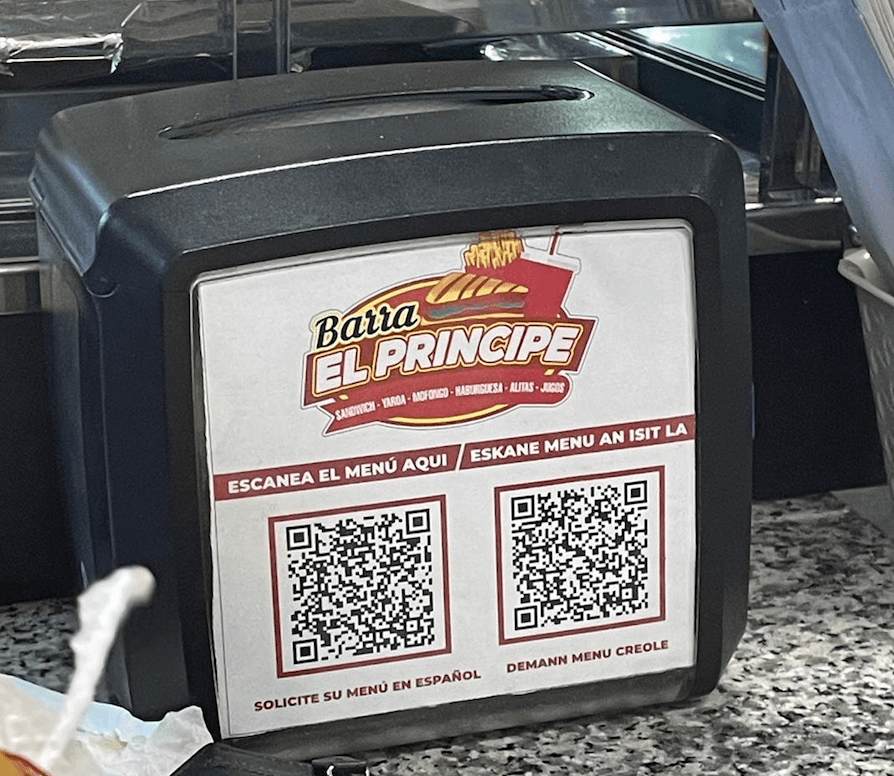

Dominican Republic

The Caribbean is exceptionally suited to explore questions of migration and multilingualism. It is considerably multilingual, with over 70 languages spoken or signed in the region, including colonial European languages as well as many unique creole languages and contact varieties that are not spoken anywhere else in the world. Though the Caribbean islands are often thought of as areas of emigration, historically it has been a region of extensive mobilities from one island to another: through enslavement, trade, and tourism. Because of how multilingual the region is, crossing a transnational boundary in the Caribbean almost always entails crossing a linguistic boundary as well, and Caribbean migrants confront a dizzying array of policies and accommodations as they move through the archipelago.

Ports of Entry: Language in Caribbean Migrations (In progress, University Press of Mississippi) is an anthology that offers a critical consideration of how language is used by both migrant groups and their host countries for negotiation, intimacy, and cultural production in the Caribbean. It brings together scholars, journalists, teachers, and community activists who approach the Caribbean from varied methodological approaches. Each of the eight chapters in the volume provides an accessible case study of the on-the-ground linguistic situation of a distinct Caribbean nation, including Haiti, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Belize, Guyana, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and New Orleans, the “northernmost Caribbean city.” These chapters offer us the opportunity to peek into peoples homes, workplaces, and schools in order to see how migrants negotiate and confront language barriers in their day-to-day lives and how Caribbean languages are being shaped as a result.